When the Supreme Court Says “No”

A writ of mandamus doesn’t happen by accident.

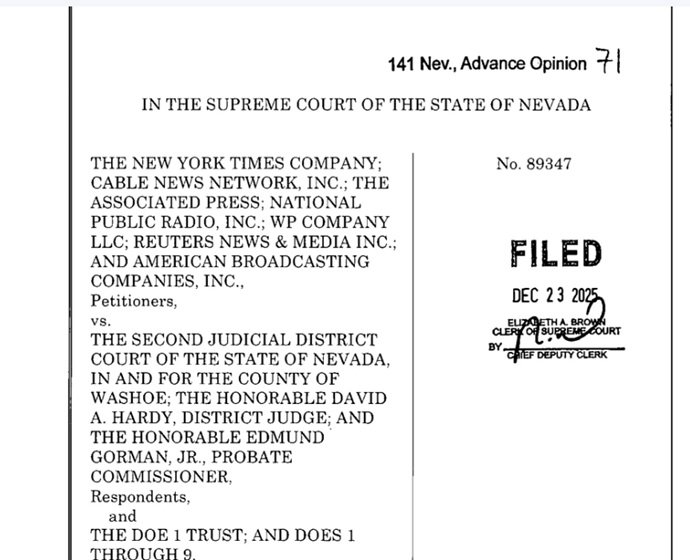

When the Nevada Supreme Court issues a writ regarding a Second Judicial District Court judge, it’s not a routine paperwork error or a harmless disagreement over procedure. It’s a public, written reminder that something went wrong badly enough to warrant correction from the state’s highest court.

And in this case, the mistake belongs to Judge David Hardy.

Hardy—who has been on the bench since 2005, first by appointment to family court and then elected without opposition in 2010 to general jurisdiction so out of family court—was reversed over his handling of the sealed Murdoch case files. Files the public had every right to scrutinize. Files that remained hidden while the Murdoch family enjoyed a level of accommodation most litigants can only dream about.

This wasn’t about nuance. It was about secrecy.

Nearly the entire local bench will soon be running for re-election, and many of them—once again—will likely be unopposed. Not because they are universally admired, but because private practice attorneys rarely want to take a significant pay cut to become a judge.

So we get longevity instead of competition. Comfort instead of scrutiny. And, sometimes, judges who stop worrying about being wrong.

The Hardy decision fits a broader pattern of preferential treatment for the Murdoch family that has become impossible to ignore.

Special parking spaces courtesy of Sheriff Darin Balaam

A dedicated courthouse entrance arranged by the Clerk of the Court

Sealed records signed off by Judge Hardy

Most defendants don’t get VIP access to the justice system. The Murdoch’s did.

That matters.

Judge Hardy has been on the bench for two decades. That alone doesn’t make him unfit—but it does make mistakes harder to excuse.

At least Hardy hasn’t lingered quite as long as Judge Connie Steinheimer, who has occupied a judicial seat since 1992. Yes, 1992. Over three decades on the bench, largely insulated from meaningful electoral challenge.

This is the downside of a system where judges run unopposed:

Fewer fresh perspectives

Less incentive to justify controversial decisions

More room for institutional favoritism

Eventually, fatigue sets in. And fatigue leads to errors.

The Nevada Supreme Court exposed a weakness in our local judicial ecosystem.

Judge David Hardy made a mistake. And now the public has a responsibility to remember it.

Because judges are not supposed to accommodate powerful families.

They are supposed to apply the law evenly—parking spaces, entrances, court files, and all.

Elections are coming. The bench will ask for trust. This reversal is a reminder that trust should never be automatic.

And secrecy—especially when it benefits the well-connected—should never be the default.